When designing any system: an app, website, or service, we often hear about two types of design disciplines: UX and UI. Though the two overlap in thinking and sometimes execution, there are many distinctions in the mindset of each approach, and how they come into play in the development of mobile apps. Dive in with our UX Research & Design expert, David Lewis, to explore the UX approach.

At its heart, UX design is the understanding of how someone uses an app, service, or system, across its lifecycle. The practice needs to anticipate users’ actions and interactions and apply that knowledge to make the experience as relevant, easy, and satisfying as possible.

A successfully designed application will allow people to complete key tasks swiftly and with a minimal amount of friction while meeting accessibility requirements. Working with a UX designer can help achieve strategic business goals. This can include increasing conversion, reducing strain on customer service, and increasing key aspects of an experience: trust satisfaction, and confidence.

The UX designer should be involved in a project as early on as possible. The first conversations with a client can yield clues as to the overall goals the experience should strive for, and the direction research can take.

The UX Design Process

1. User Research

The beginning of a project cycle often begins with discovery. This is where UX and Strategy lay the groundwork: key business objectives are communicated and refined as we begin to see what activities will allow us to gather the right information from users. We collect what we know about them: how complete is the picture, and what’s missing? User research aims to fill in these gaps through various activities and methodologies, with the goal of learning how to design the right thing through what users demonstrate to us—directly or otherwise.

Some methods, like Qualitative Interviews, are almost always useful. These semi-structured conversations are designed to generate what we want to know – and (arguably more importantly) what we didn’t think we needed to know beforehand. This method even helped one of our long-time clients prioritise their backlog of planned features. We performed two rounds of qualitative interviews, both with subject-matter experts (SME) in the company and key customers who use their software on a regular basis, which led us to identify primary and secondary factors that drive the importance of the feature. This was translated to a scale representing the impact the feature would have on their customer base. Through this, we were able to paint an effective picture of their product’s future.

Other methods such as Contextual Inquiry bring us directly into the user’s environment, where we can observe, discuss, and learn from the clear and implied actions one must take in carrying out relevant tasks.

It would be a costly mistake to bypass user research, as it is always more effective to develop something viable the first time, as opposed to changing things once the real needs of users have been discovered.

" Existing marketing personas and general customer knowledge does not provide sufficient data to justify skipping the discovery of the true nature of your customer needs, behaviours, and expectations, which will result in a much more successful product. "

The user insight data is designed to be gathered in such a way to facilitate analysis and synthesis of that which will inform the rest of the design process. The insight is translated into more tangible elements: Mindset-driven profiles communicate how a user’s needs drive the way they approach a product, and Customer Journey Maps illustrate how someone experiences the different touchpoints of a product over time.

2. Flow, Structure, and Layouts

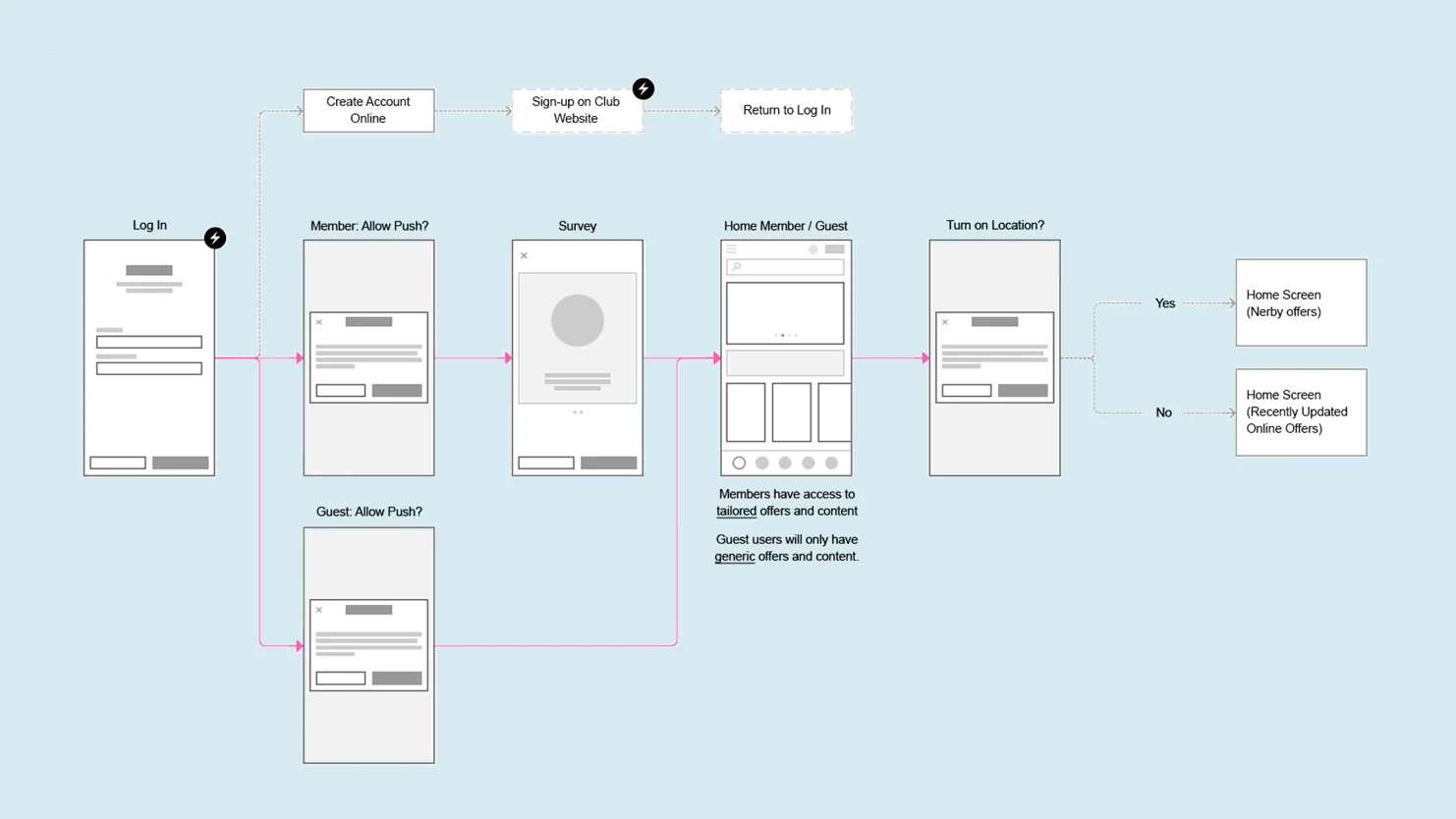

User research outcomes act as a guide. With them we can outline the goals of the experience—what we want people to feel or take away. The user flows depict what people encounter (pages, screens, etc.) as they accomplish their goals. The information architecture maps out the content into the structure of the app or system.

Then comes what people will see: the screen-level wireframes. These skeleton-screen layouts and the way to navigate between them are shown in a lower fidelity. They allow everyone in the project (including the client whose feedback will be incorporated) to understand how things are arranged and how things are accessed. The polished designs from the UI designer come later, after client feedback is addressed. All of this happens while referring back to the research outcomes: will this work for this mindset? What else are they considering at this stage?

In an AGILE environment, the design flows with the rhythm of development, section-by-section. The designer is in communication with the product owner and development team as new details or realities emerge and adjustments need to be made, through daily touchpoints.

User testing of the design should happen as early as possible in the process to learn what is or is not working about the direction to date. This can mean isolating and testing scenarios in specific parts of the product as it is designed, or testing with a more complete prototype. Not every element of a system needs to be tested, but it is quite normal that some parts or flows, especially innovative ones, are deemed a bit riskier and warrant testing. Discovering better ways to do things in the context of the new product and before development can prevent lost time and lost budget.

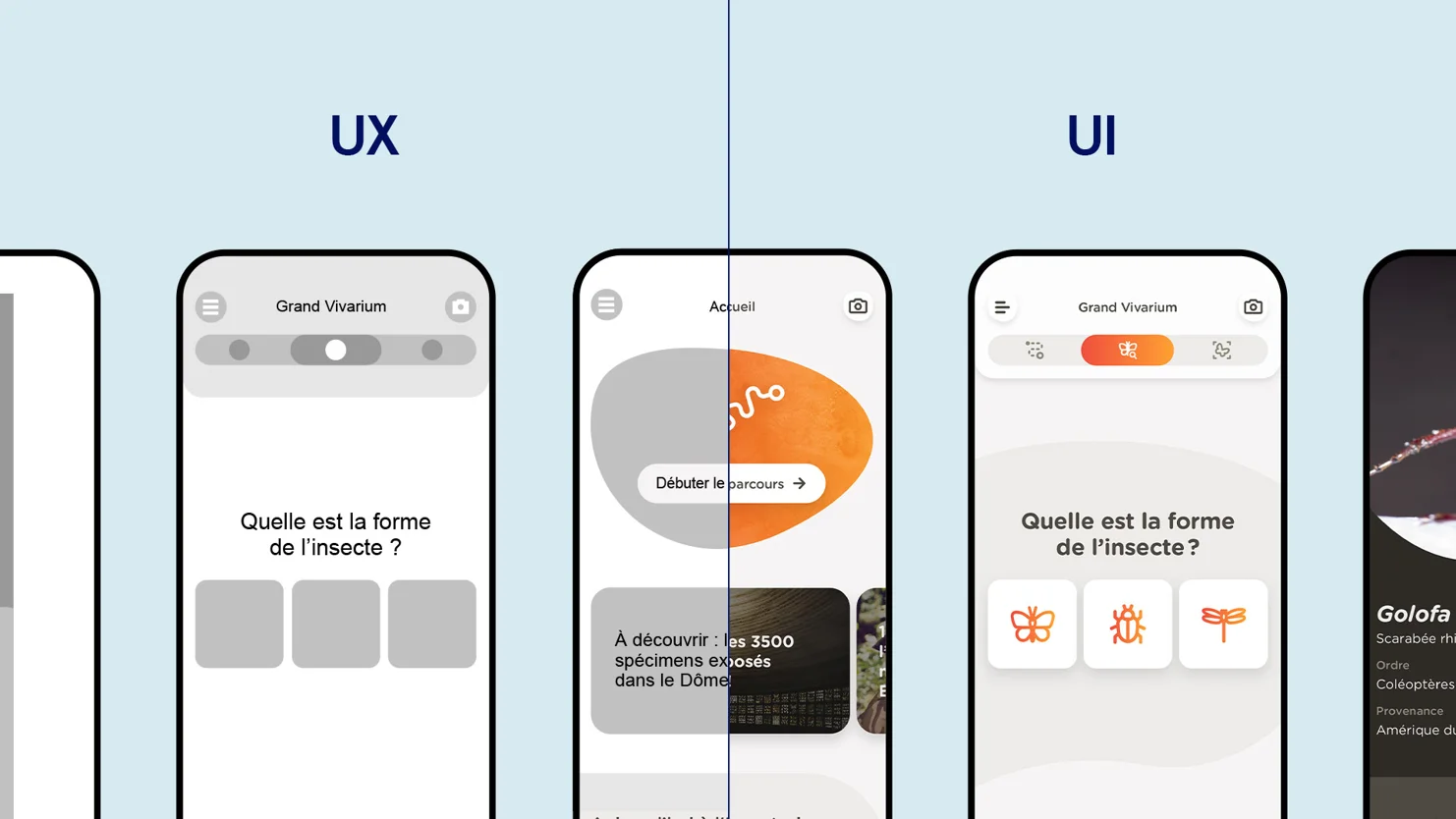

What is so Different About UX and UI?

Generally, a UX designer will focus more on the overall experience quality and consistency, with an interest in how the flow, structure, and interactions make the product successful. The UI designer approaches from the visual side of things—the beauty and finesse—collaborating with UX at the screen detail and interaction level. Both are concerned with how the user feels and what the business is getting out of the product or service.

These disciplines do not exist in a vacuum, but rather work in tandem as a project moves through design and development sprints. In a given day these two designers can be discussing improvements to screens done in a previous sprint, reviewing fresh concepts for new screens in the current sprint, and advising developers on handling new complexity that might emerge in QA.

Making the Difference

Keeping the user in-mind is key throughout a project’s lifespan. UX design is oriented in this way of thinking: gaining user insight through sound methodology as early and as often as possible is what makes the initial business goals a success, and sets the stage for continuous improvement.

“The wealth of project experience possessed by our design team enables a flexibility that can make the difference in a project’s effectiveness and efficiency. Being able to select the right research and collaboration methods means getting deeper user insight and putting it to work for the best.”