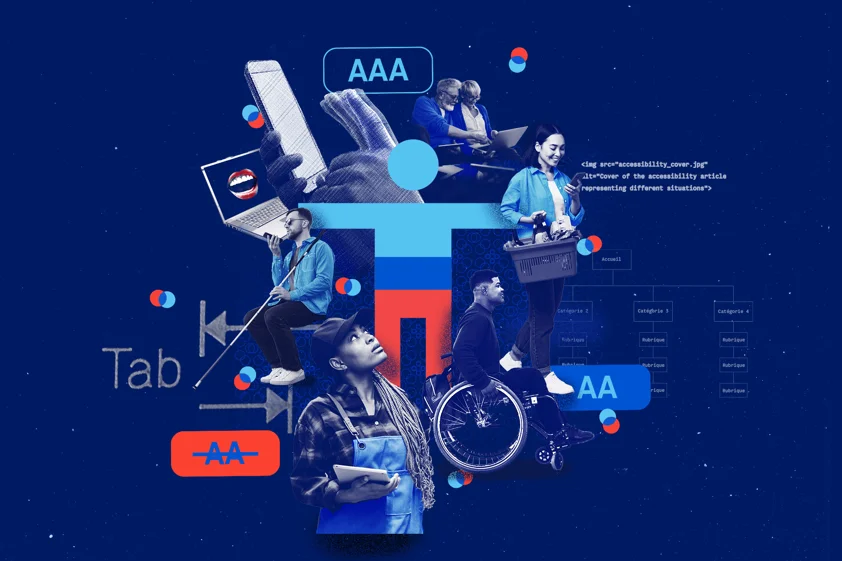

Any digital solution must meet the needs of every type of user. Understanding and respecting these needs starts right at the user experience (UX) design step. Harry Beejan, UX designer, takes the lead on our content series about accessibility in our digital projects.

Here are the topics covered in this article:

- Looking Back with Clarity: A History of Accessibility and UX Design

- Multiplicity on All Levels: Being Accessible in Every Digital Environment

- Richer and More Beneficial UX Design Process

- Preparing for Tomorrow: UX and Accessibility Next Steps

Looking Back with Clarity: A History of Accessibility and UX Design

In the early days of web design, the design possibilities were confined to what HTML coding could deliver and limited by bandwidth (remember dial-up?). As a result, websites were small in terms of navigational depth and simple in terms of design and layout. The benefit was that these types of websites offered ease of use when it came to accessibility. People who were visually impaired could change the resolution of their screens or boost the font size. Page layouts were simple enough for screen readers to scan. Even scrolling through a page and navigating with only a keyboard (using the tabs and arrows) was simple enough.

As household internet bandwidth increased and computing power was becoming more affordable, naturally, websites evolved. They began to use a richer colour palette, a wider choice of typefaces, detailed imagery, photographs, animations, videos, and even complex interactions similar to videogames. Unfortunately, accessibility was put aside during these times, as designers were more focused on leveraging these technological advancements and delivering high-impact websites.

A demand for accessibility rose from this technological explosion, which mainly impacted access to information and services. This forced all of us in the tech industry to take a pause and look at who we were designing for. A user with special needs may want to plan and book a vacation online; sign up for cable TV and select their channel package; or update their home address for their energy provider. These are basic services that should be accessible to a wide audience with varying degrees of ability.

Thanks to regulatory bodies like the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) and its development of the WCAG standard (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines), designers can refer to a set of rules to apply to their designs. Things like offering larger text options for easier reading; avoiding text in image files that can’t be translated by screen-reader software for the visually impaired; or optimizing the colour contrast for important elements on the screen to accommodate those with colour blindness.

Multiplicity on All Levels: Being Accessible in Every Digital Environment

In the past, most of our efforts as designers were to optimize the visual aspect of our products to meet accessibility requirements related to the display of information. Today, as UX designers, we have a better understanding of how to optimize the overall digital (and physical) experience. We know it’s not limited to colour contrast and text sizes. We know there are more disabilities than only vision and hearing issues. There are a lot more technology, disabilities, and regulations to consider when creating digital products now, and therein lies the multiplicity.

Gone are the days when we only needed to support Internet Explorer for Windows desktop! We now need to support multiple operating systems (Windows, MacOS, iOS, Android), web framework platforms (like Angular, Bootstrap, Vue.js), browsers (like Chrome, Firefox, Safari), and platforms that include computers, tablets, mobile devices, and even watches.

Thanks to the many technological innovations, especially in the mobile environment, a wider audience now has access to information and software. This includes people with different levels of vision, hearing, motor, and cognitive abilities. They can have various backgrounds, education levels, age groups, etc. These users are not only sitting at their desks: they are everywhere! They are connected to a digital lifestyle while walking to work, riding the bus, lying on the beach, and so much more. Civil engineering has made steps towards improving accessibility situations, like handicap parking spots and wheelchair access ramps.

«It is now up to the UX designers to provide accessibility innovations in the digital space.»

With the many platforms on the market and the wider audience, it’s no surprise that more criteria have been added to the WCAG standard. In fact, this is an ongoing process, even to this day. These guidelines take into consideration how users perceive and understand the content they have access to, and how the product can be operated at the users’ convenience and provide robust support for their preferred input methods. They also provide details to optimize the ways to design, to structure digital content and navigation, to improve content creation, to develop cross-platform interactions and to support input devices.

Finally, we can now see a wide adoption of accessibility regulations in the world. There are now more jurisdictions that are attentive to the needs of their population, and those include equal access to information for all. The province of Ontario, Canada, has implemented its AODA (Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act) regulation for most business sectors. Many governing bodies will enforce regulations for their public sectors to comply to accessibility requirements, including the UK and the USA.

Richer and More Beneficial UX Design Process

The complexity of the digital landscape has encouraged us to create a more elaborate and robust design process. As UX designers, we’re not only doing site maps and wireframes.

«We want to ensure the products we design truly meet the needs of the users.»

This process begins with research, problem definition and solution strategy, followed by content design, user flows, and the familiar things like site maps and wireframes.

When doing research, there are many things we’re trying to learn depending on the requirements of the project, including the industry, trends, competition, and of course, the target user. We want to understand the platforms they prefer, the type of information they’re looking for, how they think and feel, and even their limitations. When gathering these data points, we are already addressing accessibility by empathizing with the user and better understanding their context. Ultimately, we are trying to determine what problem we’re trying to solve and to address the user’s needs.

Once we’ve gathered the research and we understand the user’s needs, we build the solutions strategy for the product. Maybe the product needs to help users make better financial decisions, find deals on retail items, chat with a mental health specialist, or even assist with a flat tire. Much like the WCAG standard, we determine the complexity level of what we’re building, and how the user can access these features with ease.

Content is another area that UX designers are becoming more involved in. Some content specialists even identify as UX writers, as the need for optimized and accessible content is on the rise. It’s not only about search engine optimization (SEO) and marketing goals… The WCAG standard and regulations like the ones from the government of Canada’s Financial Consumer Protection Framework provide guidelines and require that content be optimized for structure (headings and paragraphs), simplicity (only essential information) and understanding by a wide audience (avoiding overly complex language). Since UX designers have a deep empathy for the user, they are well positioned to provide guidelines on who the content speaks to and what it should accomplish for the user.

Accessibility doesn’t stop at the high-level UX design stage. When building the site navigation, the hierarchy needs to be well-thought-out, which is why we do information architecture exercises. The users need to be able to find the content and the location they need in a way that makes sense to them, with little cognitive load. When considering the technical requirements for screen readers, the navigational structure needs to be easily read and understood by users who are visually impaired. When defining user flows and form designs, we try to minimize the complexity of the interaction. What is included in the entire flow, the steps involved in the process, and the validation on the actions they take all need to be clear for the user. These are usability best practices that we have always employed and that have now become essential to accessibility.

When it comes to detailed UX designs (wireframes), that’s when the screens begin to take shape and the structure of the page has an impact on accessibility. Users who navigate with screen readers need to be able to jump to the location of the screen without reading every little detail of a header, navigation bar, body text, or page footer. The screen layout is divided into landmarks, which the user can quickly tab through, before going into the details they wish to read. Even the structure of a content page is well defined, thanks to heading levels and body text descriptors. We also ensure that these pages display properly on a wide variety of devices at varying zoom levels. At the page’s component level, we evaluate the use of colour, iconography, text, and shapes. The affordance of these elements can differ greatly between users and platforms, and as UX designers, we study these elements carefully. The UI designer is also integral at this level of detail, as they will be the ones determining the use of colour palette, typefaces, and iconography. They will ensure colour contrast and text sizes are WCAG compliant.

Preparing for Tomorrow: UX and Accessibility Next Steps

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is already working on the next phase of guidelines, and more regulation will be in place in more jurisdictions, not to mention the penalties that will come with non-compliance. It’s not only a matter of convenience anymore, applying accessibility requirements will become law. The next generation of guidelines will refine what is currently there and be addressed to new segments of the population. Of note is the support for varying education levels, neurodiversity, cognitive ability, mental health issues, and general health issues. The addition of these segments broadens the audience’s scope so much that almost anyone will be able to identify as a person with special needs.

Thanks to our design process, we are ready to tackle the accessibility challenges of tomorrow. In doing these design exercises, we understand the users who access the information and who seek to benefit from these digital products. The goals are to accompany the users, provide them guidance, inform them, and empower them, particularly those with disabilities and special needs. This will ensure everyone is on an equal playing field, and this is the greatest benefit of electronic platforms in our digital age.